Fractured Medical Care: A Rant Constructive Criticism from a Patient Who Cares

I am incredibly lucky to have good health insurance and live in an area that offers first-rate medical care. These are both privileges many do not share and I don’t take either for granted. But, it’s in my nature to kvetch a bit and offer constructive criticism (just ask my husband), and with all the hours spent in doctors’ offices these days, I’ve had ample opportunity to observe and critique.

I find the fractured nature of our medical system incredibly frustrating. Before I got sick, this was mostly a theoretical issue for me. I rarely went to the doctors office. However, since my diagnosis, I visit doctors like it’s my job (it kinda is). In the past 15 months, I’ve consulted with a general oncologist, a thoracic oncologist, an integrative oncologist, a pulmonologist, a cardiologist, a surgeon, a primary care doc, a palliative care doc, a psychologist, a couple Traditional Chinese Medicine docs, and more … I even went to a podiatrist in the midst of all this, because dammit if my feet didn’t hurt while my lungs were trying to kill me. Do you know how many times any one of these doctors has talked with another? To my knowledge, zero.

Ok, fine. The podiatrist gets a pass. The neuroma in my foot has nothing to do with my lung cancer. But every other medical appointment I’ve gone to in the last 15 months does relate to my lung cancer, and when none of the doctors are talking to each other, that leaves me to oversee it all. The various doctors can (sometimes) access notes in the file, but it falls to me to relay and incorporate much of the content and context. And guess what? Other than having more of a vested interest in this than anyone else, I am sorely ill-equipped for this job. I don’t know my hemoglobin from my hematocrit. I can hardly differentiate the images of my lung scans from the sonograms I had of my children in utero (my lungs are super cute). I’ve not only never had cancer before, I’ve never had any serious medical issues. So, now I’m supposed to be in charge? While I’m feeling like crap and reeling from a total life upheaval? This is the system? Are you freaking kidding me?

Recently, I had a fleeting moment of hope that I might receive help managing the complex mix that is treating advanced cancer. My oncologist referred me to the Stanford Integrative Clinic. Maybe this was the answer – a doc who’d affirmatively signed on to “integrate” care! Perhaps she’d help me oversee everything, make sure the acupuncturist was copacetic with the oncologist and the cardiologist, etc.

The location of the clinic’s building should have been a tip-off: Stanford’s version of Siberia, the Integrative Clinic sits at the very edge of campus, the furthest possible building from the hospital and cancer center. It turns out the Integrative Clinic simply offers acupuncture; to bolster their “integrative cred,” they play meditative music on a little boom box stashed under one of the waiting room chairs — oooommm, nice try.

It strikes me as so odd that the medical system works this way. If I were building a house, I’d have a general contractor to oversee all the specialists (the electrician, the plumber, the carpenter, etc.). Most businesses I can think of strive to provide customers with a cohesive product or service. But, when I asked my primary care doc if she could fill this role, she demurred. Helping manage the complicated care of an advanced cancer patient was out of her scope. Ditto with the palliative and integrative docs. Everyone, it seems, has carved out their little piece of the pie and is disinclined to trespass on another’s. Why is medicine like this, with a million little fiefdoms, each isolated from the other, requiring the patient to bridge the gaps or tiptoe across the egos when there are overlaps?

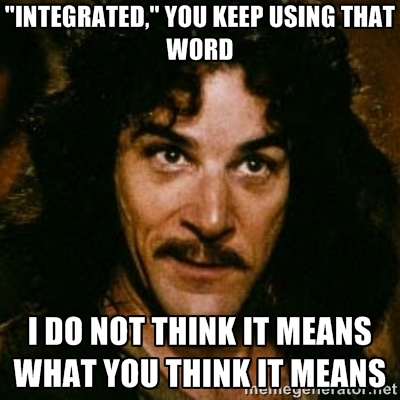

A quick perusal of websites and brochures for many major cancer centers indicates that at least the marketing departments know that patients value an integrated approach. Cancer Treatment Centers of America proclaim on their homepage “Integrative Cancer Care with You at the Center.” The first item listed in Stanford Cancer Center‘s mission is “comprehensive patient care,” and also repeatedly mentions a “team approach.” Radio ads for Kaiser Permanente trumpet how they’ve put everything under one roof to provide patients with coordinated care. And, I’ve never really understood Sutter Health’s “We Plus You” slogan, but I think they’re trying to peddle the same cooperative concept. The problem is, of course, that it’s easy to slap buzz words like “integrated,” “comprehensive,” and “team approach” on marketing materials, but it’s quite another to effectuate them in real life.

To be honest, I’m not sure what’s the best solution. I’m not looking for another layer of bureaucracy – some desk jockey/key master who must supervise and approve every move a patient and her doctors make. Yet, patients with complex medical situations need someone knowledgeable to help navigate this overwhelming landscape. There is some precedent for integrated care in our western medical system. One example are tumor boards, where a number of doctors who are experts in different specialties review and discuss the medical condition and treatment options for a patient. Tumor boards demonstrate that a multidisciplinary, cooperative approach is possible, although they are currently used only in a narrow subset of cases and I’m not sure how scaleable that model is. A second example are GCMs. “GCM?” I asked when I heard the acronym for the first time last week. “Oh, that’s ‘Geriatric Care Manager,’” my friend replied, “it’s a big thing now, because so many elderly people need help coordinating their complicated medical care.” Wow, that sounds like what I’m looking for. Do I have to be geriatric to get one of those?

Perhaps tumor boards and GCMs can provide a starting point for talking about how medical providers might put some substance behind their marketing claims. I see healthcare providers spending billions, building first-rate physical facilities all around me. But, if they don’t improve the coordination of services inside them, we’re missing a big part of the equation. Again, I want to reiterate: I’m so very grateful to receive the health care I do. I am incredibly lucky. But if I may be greedy, in my ideal world, I’d like to see true integration, where doctors talk to each other a little more and patients with complex cases have meaningful help overseeing it all. That’s my dream for tomorrow, anyway. Today I’m going to settle for a little more of that meditative music, please.